College of Nursing Professor Pioneers Breastfeeding Research in Kentucky

By Sally Evans

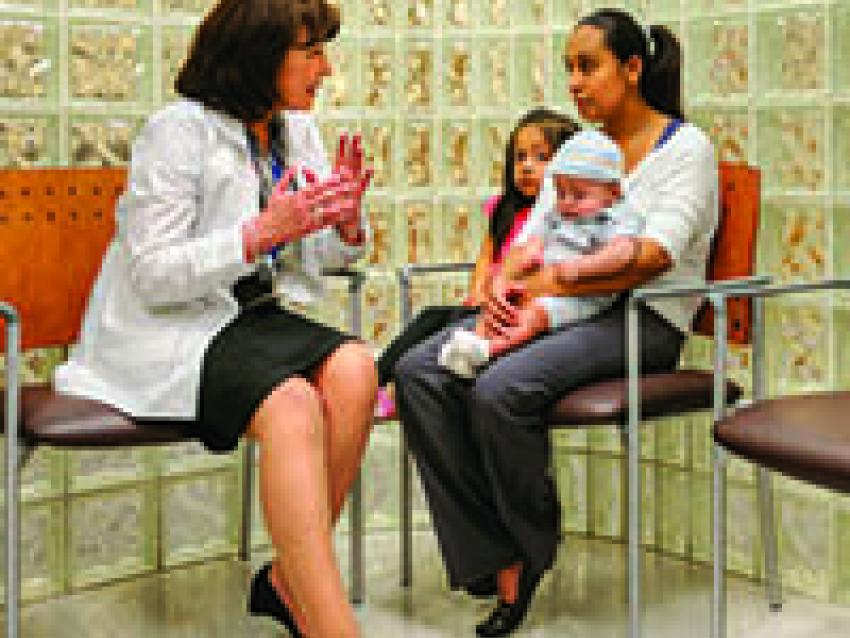

Assistant Professor Ana Linares, DNS, RN, IBCLC is breaking new ground as the only nurse researcher to study human lactation in Kentucky—at UK’s very own College of Nursing.

Dr. Linares, mother of four and grandmother to six, first collaborated on a project to study factors associated with health decisions of Hispanic women in Lexington after moving to the U.S. from Arica, Chile in 2009.

“I focused on the Hispanic population because I knew that they would feel comfortable with me,” she says.

According to Dr. Linares, Hispanic women are more likely to face additional stressors—including language barriers, cultural beliefs, mistrust and sometimes immigration issues—that may prevent them from sharing personal information with health providers, including nurses, and researchers.

“This population is part of our community. They are having children and the only way we can help them protect their infants or prevent them from getting sick is by promoting health from the very beginning—from the moment of birth,” says Dr. Linares.

She and her colleague, Cristina Alcalde, associate professor in Gender and Women's Studies, found that many Hispanic women claimed to be more knowledgeable on health decisions after coming to the U.S., yet they were determined to feed formula, in addition to breast milk, if they had children.

“They told me it was a decision based on information they were getting – information that was completely wrong,” says Dr. Linares. “They believed that formula had important nutrients that you cannot find in breast milk.”

Breastfeeding Research

Inspired by these misinformed responses, Dr. Linares decided to focus specifically on breastfeeding among Lexington’s Hispanic population.

“The Hispanic population is extremely health-vulnerable and at high risk for diabetes, obesity and many other diseases when they arrive in the U.S. because their food and eating habits change so dramatically,” says Dr. Linares. “Exclusive breastfeeding practices, or breastfeeding without any additional formula, directly aid in the prevention of such diseases.”

Her study included 100 participants whom she followed from the time the mother was told she was pregnant until four months after delivery. She studied factors such as the mothers’ intention to breastfeed, social support, family support, health provider support and also how confident the mothers were with breastfeeding.

Linares discovered that 98 percent of the women participating in her research initiated breastfeeding during their hospital stay. Of those, only half of them were breastfeeding exclusively. The other half requested formula.

“They come here from another country, and they have this belief that if Americans believe it is normal to formula-feed, then it must be a good practice,” she says.

Several organizations, such as the World Health Organization, the American Academy of Pediatrics, UNICEF and the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee suggest breastfeeding exclusively for an infant’s first six months. Additionally, many researchers report that by breastfeeding only decreases the infant’s risk of obesity by 24 percent and the risk of infection, especially gastrointestinal infection, by about 64 percent.

“If the mother starts formula-feeding, the infant will become full and will no longer require milk from the mother. This lack of stimulation, or skin-to-skin contact, will cause a decrease in the amount of milk the mother is producing,” says Dr. Linares. “The stimulation is really important for the mother, her child and the breastfeeding process.”

Current Initiatives

The National Institutes of Health is currently reviewing Dr. Linares’ proposal to receive funds for an intervention with Hispanic women in Kentucky for which she plans to follow 70 participants throughout their pregnancies and childbirth.

Her intervention has two aims: to develop a community-based program to help Hispanic mothers manage breastfeeding and, therefore, lower early childhood obesity risk; and to determine the feasibility of a community-based intervention delivered by bilingual and bicultural International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) to extend the duration of exclusive breastfeeding in Hispanic women.

Dr. Linares is also working with the Kentucky Hospital Association to distribute surveys to every birthing center in Kentucky to learn how they implement Skin-to-Skin Care, which is characterized by direct contact between and the mother and newborn for physiological and psychological bonding.

Her work does not stop there. Dr. Linares is collaborating with the Kentucky Department of Public Health in Frankfort, Kentucky, to conduct another survey that will help implement a breastfeeding-friendly policy for childcare facilities in north-central Kentucky. The survey examines how childcare facilities support mothers who are breastfeeding and what the University of Kentucky can do to help implement policies that outline effective steps to support these mothers and their children.

"Her contribution to neonatal health is vital for the well-being of infants and mothers,” says Dr. Janie Heath, dean of the College of Nursing and Warwick Professor of Nursing. “We are extremely proud to have her at the College of Nursing.”